Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS): An Overview

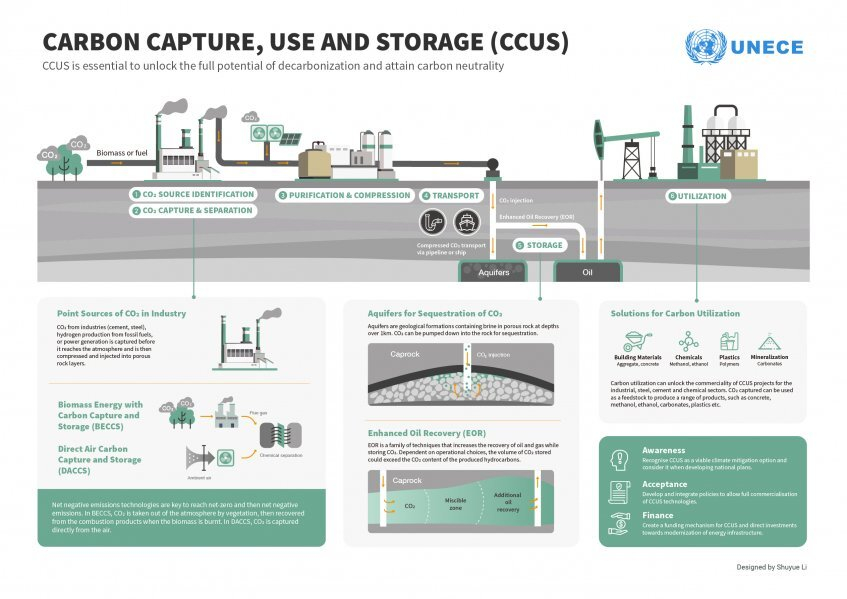

Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) is increasingly recognized globally as a pivotal strategy for curbing CO₂ emissions from industrial and energy sectors. As of now, there are 77 commercial carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects operational worldwide, collectively capable of capturing 64 million tonnes per annum (Mtpa) of CO₂. The fundamentals of CCS involve capturing carbon dioxide at emission hotspots, transporting it, and injecting it into deep geological formations for permanent storage. This technology plays an essential role in addressing climate change, especially in sectors where emissions reduction via renewable energy alone is unfeasible.

Kazakhstan’s Carbon-Intensive Landscape

Kazakhstan is one of the world’s most carbon-intensive economies, heavily reliant on fossil fuels and energy-intensive industries. While the country currently lacks a robust legal or regulatory framework specifically for CCUS, it has made ambitious climate commitments, including achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. In anticipation of these goals, supportive regulations are expected to materialize in the coming years. For project developers and investors, understanding how CCUS initiatives align with existing legal structures is crucial.

Geological Formations Suitable for CO₂ Storage

Globally, several deep geological formations have been identified as suitable for long-term CO₂ storage. Two significant types relevant to Kazakhstan are:

-

Depleted Oil and Gas Reservoirs: These well-studied formations offer favorable geological characteristics like porosity and permeability, which have been evaluated during years of hydrocarbon extraction. Existing infrastructure such as wells and pipelines can often be repurposed for CO₂ injection. Moreover, CO₂ injection could enhance oil recovery (EOR), boosting the economic viability of initial CCUS projects.

-

Saline Aquifers: These formations contain highly mineralized water at depths greater than 800-1000 meters—water that is not suitable for drinking or industrial use. Kazakhstan has extensive saline aquifers, and international bodies like the IPCC regard them as one of the most promising options for long-term CO₂ storage due to their large capacity and widespread availability. While salt domes also present potential storage options, current Kazakh legislation lacks a comprehensive licensing regime for their usage.

Image credit: UNECE.

Regulatory Framework for CCUS

The regulatory landscape for CCS has evolved significantly across various jurisdictions. Norway laid the groundwork in 1996 with the launch of the Sleipner project, relying on existing petroleum laws to regulate offshore CO₂ injection. This multi-layered framework involves securing a range of licenses—from petroleum licenses for reservoir access to pollution control permits for CO₂ injection and monitoring during post-closure, creating a model that has influenced CCS legislation globally.

In the United States, a complex federal regulatory framework emerged, starting with foundational laws like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the Safe Drinking Water Act. A key milestone was the introduction of Class VI well requirements by the EPA in 2010, setting stringent standards for geological storage, monitoring, and financial assurance. U.S. CCS projects must navigate both federal and state levels, which complicates the regulatory landscape but also illustrates a comprehensive approach to balancing environmental concerns with energy needs.

Australia, the EU, and the UK have also taken substantial steps in regulatory development, creating frameworks that incorporate environmental monitoring, operational permits, and long-term liability for CO₂ storage. Each region’s approach reflects local conditions and policy priorities, paving the way for increased CCUS adoption.

CCUS Development Strategy in Kazakhstan

While Kazakhstan does not yet have a designated law specifically governing CCUS, its strategic vision acknowledges CCUS as critical for achieving national decarbonization objectives. The government’s strategy aims for a 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and 95% by 2060 compared to 1990 levels. A significant focus is placed on transitioning to renewable energy sources, modernizing energy infrastructure, and deploying low-carbon technologies.

Key pillars of Kazakhstan’s low-carbon transition strategy include:

-

Decarbonizing Fossil Fuel Industries: Implementing CCUS technologies in coal-fired power plants and energy-intensive industries is essential for achieving emissions targets.

-

Decarbonizing Non-Fossil Fuel Industries: Expanding the adoption of technological advancements in various sectors that contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

-

Enhancing Natural Carbon Sinks: Developing industrial technologies for carbon capture, utilisation, storage, and sequestration while fostering natural carbon sinks.

As the country strategizes, it prioritizes energy and industrial sectors, which account for most of the national emissions.

The Legal Landscape for CCUS Implementation

The absence of a dedicated CCUS regulatory framework in Kazakhstan does not preclude the legal avenues for project initiation. Currently, the Environmental Code references “carbon dioxide capture” as an activity needing permits, categorizing it as a Category I hazardous facility. This acknowledgment potentially sets the stage for a regulatory framework geared towards CCUS technologies.

Though the current Subsoil Use Code doesn’t explicitly regulate CCUS, various existing subsoil, environmental, and water regulations offer a minimal yet workable foundation for pilot projects. The Kazakh legislation could adapt models from Norway and other regions to lay down the groundwork for initial CCUS activities.

Navigating Regulatory Uncertainties

For effective implementation, project developers need to navigate the complexities of various laws in Kazakhstan. The Subsoil Use Code provides theoretical avenues for licensing underground storage, with two primary options under consideration:

-

Underground storage facilities for hydrocarbons: While this is not directly applicable due to the focus on man-made facilities rather than geological formations, it serves as a conceptual starting point.

-

Licensing for the storage/disposal of liquid waste: This option may offer a more legally feasible pathway for CCS operations, where injected CO₂ could be interpreted as a disposal of liquid substances into the subsoil.

The classification of CO₂—whether as waste or otherwise—remains a pivotal issue. Current legislation does not explicitly categorize CO₂ as waste, yet under certain conditions, it could fall under such definitions. This classification directly impacts the regulations governing monitoring, reporting, and long-term liabilities in CCUS projects.

Investment and Future of CCUS in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan’s commitment to integrating CCUS into its energy transition strategy is evident through its ambitious climate goals. The evolution of a comprehensive legal framework is pivotal for attracting investment and reducing regulatory uncertainty. Future developments will need to address CO₂ classification, permitting requirements, long-term liabilities, and how CCUS activities intersect with existing legislation on water and waste.

By strategically resolving these issues, Kazakhstan can create a conducive environment for CCUS adoption, essential for achieving its long-term carbon neutrality goals. As the country transitions, its approach may also serve as a blueprint for other developing economies aiming to leverage CCUS technology in their decarbonization efforts.